In the video below, there is a discussion with Terry Gilliam, Michael Palin and Annette Badland. The event took place in 2017 following a screening of the film, and was hosted by film writer Danny Leigh on behalf of the British Film Institute.

In 2017, a new 4k restoration of the film had been created from the original camera negative, overseen by Terry Gilliam, to mark its 40th anniversary. Criterion Collection UK released a special director’s edition of the film on Blu-ray and DVD in November 2017.

Below the video are some reviews of the film at the time it was released.

Jabberwocky: Contemporary Reviews

“The film is weak in certain parts and loses its way here and there, but I’m willing to overlook all that because of the flurry of laughs it provokes about human farce and hypocrisy. King Bruno, played by Max Wall, is the character I’ll remember for a very long time; he is so funny that at times I laughed until I almost cried. John LeMesurier as the Chamberlain is not far behind and Michael Palin’s portrait of the idiot is also very funny. But judge Jabberwocky for yourself” (Derek Malcolm, Cosmopolitan).

“A strange film, entirely devoted to an imaginary universe, and which, in spite of its relative failure, borders at time on the sublime and always has a plastic beauty that makes it difficult to fit it into any given genre. In fact, what genre is it? Historico-satirico-fabulo-mythico-fairy-burlesque?” (R.B, Positif)

“What distinguishes the Pythons’ approach to the extravagant style of Hellzapoppin’ and the Marx brothers is the creation of a world of fantasy, inspired in comics and cartoons, which is extremely respectful of realist details and mixes genuine beauty and real horror in a way that evokes Bergman and Fellini” (Alan Brien, The Sunday Times).

“If Jabberwocky . . . had surfaced at some offbeat cinema club, complete with subtitles and credits stuffed with names containing more xyz’s than vowels, I would be the first to interpret it as a phantasmagoric parable foretelling the imminent decline and fall of Western civilisation… The Python humour . . . is notorious for being infantile hysterics inflated often to the level of genius, with a characteristic delight in dung, blood, insanity, mutilation, torture, freaks, indecent exposure and rude words and gestures. Much of it is intended to be nothing more than loony outrageousness . . . .But everything means something, and it can be no accident that Jabberwocky bears almost no relation to Lewis Carroll but turns out to be instead an uncannily persuasive Breughelesque portrait of the Middle Ages with many slyly snide sideglances at the modern day. For what distinguishes the Python approach from the Hellzapoppin/Marx Brothers/Goodies style extravaganza is that it creates its comic-cartoon fantasy world with immense care for realistic, tangible detail, mixing together genuine beauty and real horror in a way that is sometimes reminiscent of Bergman or Fellini. Terry Bedford’s photography would not have disgraced either…” (Sunday Times, 3 April 1977)

Terry Gilliam sat in a Soho coffee bar, blue jean legs up on the seat and wondered gloomily why the world keeps asking him about the symbolism of Jabberwocky. Out of the window he spotted two upright Englishmen in pin stripe suits and bowlers, noses tilted heavenward as they pushed through the crowds ignoring all around. `That’s what my films are about. They’re about the eccentricities, the blind absurdity of the human race. Those men might be living on another planet. “I don’t think it’s necessary to have a meaning in a film”’, he said. “I think it’s important to make people laugh and I seem to have done that. But there have been complaints about the gore and defecation – I had a girl from the radio interviewing me the other day demanding why I had done a film about defecation. “It’s really not quite like that but there are situations when people are very funny relieving themselves. There’s nothing in the film you won’t find in a Brueghel painting…” There’s a scene he must get into an animation some time. Walking down a street in Copenhagen he saw a very well-dressed conventional couple parading arm in arm, with them was a snowy white poodle with a plaster stuck over its bottom. `Amazing isn’t it – when I draw that people will say, “ah that’s not life” ‘. And he chortles all the way back to Hampstead. (`Tinkling Symbols’, Guardian, 6 April 1977)

In Jabberwocky, cheerfully announced as “at last, a film for the squeamish” – we are in the Middle Ages, which is to say we are in the middle of demolition, muddle and what might well be thought of as a right old mess of pottage. It is a world very like the world of the films of the inspired Monty Python lot, starring one of the same actors – Michael Palin playing a dim-looking youth called Dennis Cooper – and directed by Python’s Terry Gilliam, with a screenplay by him and Charles Alverson. The havoc of a kingdom we are in is ruled by King Bruno the Questionable, played by that great old English music-hall comedian Max Wall. His voice is like something being drawn up and down a nutmeg grater; he carries his orb as if he were about to lob it, and he appears to be dressed in a handmade patchwork horse blanket. Possibly the monarchical robe was made by the nuns living with his daughter, wo are all eternally stitching away, and who are named the Sisters of Misery.

Outside, medieval chaos runs amok. Slops are flung from every window. A voice rather like a muezzin’s calls “Rush hour!” and the streets immediately give way to even more push and shove than usual. Dust reigns. The palace is powdered with it. Nobody can set foot anywhere, or sneeze, without raising a cloud of it. People irritably get words wrong. The incomparably sniffy John Le Mesurier, playing the Chamberlain, calls the King “sire” and, receiving no thanks for his manners, lapses into calling him “darling.” The King has attacks of fury with the mayhem of his realm which seize him like bouts of hay fever. Having graciously congratulated his fragile daughter (Deborah Fallender) on how beautiful she looks, he sits with her and the Chamberlain at a tournament that spatters their finery with blood. There must be some better way of choosing a champion than all this carnage, the Chamberlain feels. Someone suggests hide-and-seek. So the knights, still clanking in their armor, but on foot, creep around “Henry V” – looking tents and play a game of surprise with each other. This is a world of prayers chanted to flying hogfish; of beggars who smilingly flourish bits and pieces of amputated limbs for a gracefully accepted coin; of filthy, overcrowded battlements; of a wild red-headed fanatic (Graham Crowden) preaching in a smithy that may well be a production line for the most up-to-date in Middle Age torture instruments; of a reputedly brilliant master cooper (Dennis’s father, played by Paul Curran) who hasn’t the faintest idea of how to keep the staves of his barrels together. In the midst of this buoyant shambles, a peculiar decorum reigns. Dennis Cooper, in a dreadful fight, protects himself with a painted shield that looks like a papier-mâché knickknack from a crafts shop. A knight sent out to kill the Jabberwock wears a lobster on his helmet. The monster is a cobwebby creature who, carrying out the crustacean motif, has an upper torso that seems to be definitely in the seafood line. Lower down, he gives the impression of a dilapidated bat, but he has the face of a pair of lobster crackers that has spent centuries on the top floor of the house of the Madwoman of Chaillot.

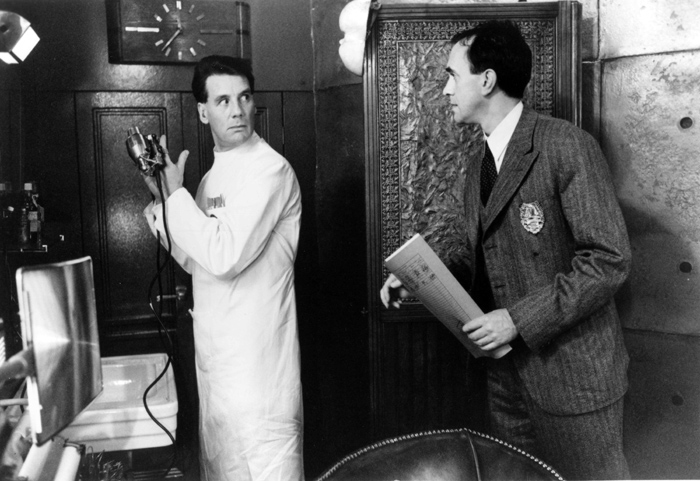

Dennis is besotted for the moment with a girl called Griselda Fishfinger. Fishfingers are an unappealing sort of frozen food in England, often fed to cats, though they are advertised happily on commercial TV as the ideal TV-watching nourishment for the family.) Griselda (Annette Badland), known as The Lovely Griselda and cast for her very large size, is a tightly corseted wench who keeps a potato in her bulging upper lacing. She speaks little but munches the potato hungrily. Dennis manages to get the potato and treats it as if it were a golden apple. Like him, everyone else in the film seems to be contentedly misled. A character will tug a door pull, and behind the door a man on the other end of the bell rope will be abruptly jerked up by the neck, screaming blue murder. “Someone at the door, dear,” a nice-looking wife will then say domestically to her husband at the fireside. The film’s citizens – even the King – put up with severe difficulties. The monarch’s trumpeter plays paeans that are impossibly out of tune, and the monarch’s drummer has an instinct for drumming interrutions to everything the royal herlad is trying to say. While the Bishop (Derek Francis) is in full flood, a dustpan is being used, as it well should be, though it is not the medieval filth that mostly bothers people but the monster, which is said to have once so scared a man that the man’s teeth turned white overnight – as, again, they well should do, the general color of teeth in the Middle Ages being rust-brown, according to this film. Still, the characters survive on the whole with amazing good temper. They are only occasionally pettish. There is a nasty moment when Dennis and the Princess are married. “I pronounce you man and wife,” says the officiating clergyman. “Princess ” corrects H.R.H on her high horse. “Jabberwocky” deserves a Lewis Carroll association; he would have rejoiced in its nincompoop wit and the blue-sky reaches of its nonsense. Not often has the rude been so recklessly funny. (New Yorker, May 9 1977)