by Tim Woo

|

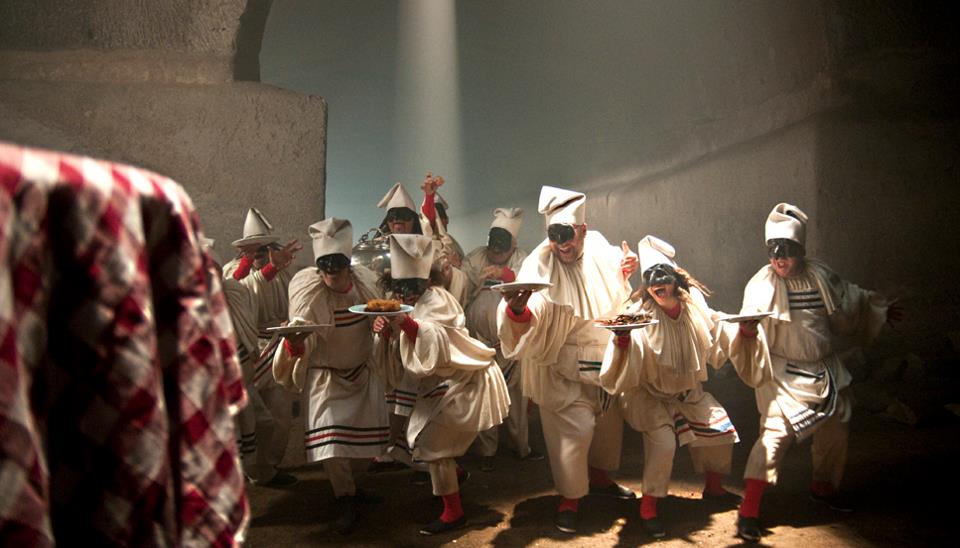

Since 1998, Mitch Cullin has published a string of highly acclaimed novels, among them the startling novel-in-verse Branches and the bittersweet The Cosmology of Bing, marking him as one of the best and most distinctive new voices in American literature. A writer who avoids publicity tours and readings, he has already established himself as something of a cult figure, working outside of mainstream publishing, and writing books that don’t fall easily into current literary trends. His recent offering is a global-spanning collection of eight longish stories (From The Place In The Valley Deep In The Forest) that has garnered the usual amount of praise, including a starred review from Booklist, and will be published next year in the United Kingdom by Weidenfeld & Nicolson. With major publishers from other countries such as Japan and The Netherlands translating his work for forthcoming editions, the 34-year-old author seems poised for even greater success beyond his own country. As a result, it’s no surprise that maverick filmmaker Terry Gilliam would take notice of Cullin’s unique worldview, a vision that mixes dark themes, humor, and a deep sense of compassion for his unusual characters.

I caught up with Mitch Cullin via telephone at his home in Tucson, Arizona. Expecting to hear the voice of a serious, intense young novelist, I was surprised by the warmth and friendliness he extended toward me, answering every question frankly and with the slight hint of a Texas accent. Often quick to digress from the subject of himself, he seemed more comfortable talking about his passion for contemporary underground bands like the desert-influenced Giant Sand/Calexico collective and Kurt Wagner’s neo-country outfit Lambchop, the unrecognized genius of the late Gene Clark, and his growing collection of import Japanese DVDs. But when director and former Monty Pythoner Terry Gilliam was brought up, it was evident that I’d found a subject that pleased him as much as his hobbies.

It’s seems you’re a lover of movies, especially world cinema, so I’m wondering if you’ve ever entertained any ideas of directing?

As a kid I wanted to be Stanley Kubrick. Wait, I take that back – I wanted to be Terence Fisher, the guy who directed a lot of those great old Hammer horror films. I had my Super 8 camera, and shot a lot of short movies with friends, things with titles like Don’t Open The Door and U.F.O. But it seems I was meant to be a writer, so one aspiration simply evolved into another. Now I much prefer just watching movies. And, in a way, being a writer of books is like being a director for the mind. When writing something, I get to do the set design, casting, work out the look and feel of the scenes, the editing, all that stuff in my head and then on paper. So I’ve got final cut, as it were. On a whim, I can even kill off the actors with total impunity if I want. But it doesn’t pay as well as film directing, I guess. But then again, I don’t have to deal with studios or countless egos, and no one is re-writing my work to suit their agenda of making potential millions. To be honest, I probably lack the social skills and logistical aptitudes required to direct anything or anyone other than myself.

Don’t you have to put up with a certain degree of compromising when dealing with publishers?

No, I’ve been pretty lucky there, especially since the books have proven themselves. Then you get known for writing odd, curious little books, and there’s quite a bit of freedom in being perceived that way. I know writers who’ve had some incredibly miserable experiences with editors and publishers, but I’ve been fortunate. Of course, a lot of that crap goes on in the larger publishing houses, which are gradually operating more and more with a Hollywood mentality. So you’ve got a lot of twenty-ish corporate types telling fifty-year-old writers what makes viable fiction. But I started out with small presses, dealing exclusively with editors and publishers who value good writing, regardless of whether it sells in the hundred thousands or not. It’s the template way of thinking that I despise the most.

What is that exactly?

You know, if something isn’t based on a successful model then it isn’t even worth considering. So Oprah recommends a book, and suddenly publishers and agents are looking for something just like it and little else. Flavor of the week stuff, right? This kind of thing goes on in Hollywood and in the music business all the time. It’s really sick, just the biggest enemy of innate creativity that I can imagine, because it forces artists to alter or stifle their own natural tendencies. It’s a dangerous thing when writers or filmmakers or musicians become caterers.

Along those lines, Terry Gilliam has a reputation for being David to Hollywood’s Goliath. Have his battles been an inspiration to you?

Again, I’ve had few battles to get my art out there. That said, I do think his uncompromising integrity has been an inspiration to many, and not only for writers and other artists. But I can’t equate my industry hardships with his, because either I’ve been incredibly lucky or it’s just that I’m not worth taking on. Also, my medium is tiny compared to his, so it’s easier to fly under the radar because there’s not millions of dollars involved. So I quietly write my books, they get published with a minimum amount of fanfare, and it’s a fairly straight line from one end to the other. If I had to deal with the kind of people he’s had to deal with while trying to get his films made, I’d probably have dived headfirst into a drained, empty swimming pool by now.

Is his interest in turning Tideland into a film a dream come true?

Well, for me it is, very much so. Although it might become a nightmare for Terry (laughs). You know, I sent him the book before it came out–when it was still in galley form–because I wanted him to see it and hopefully enjoy it, and I wanted him to know how much his work has meant to me. In a way, books are a benign way to make contact with those people who’ve been your dream weavers, and Terry is certainly one of mine. No one believes me when I tell them this, but I wasn’t trying to sell him on it as a movie. Maybe, I thought, he’d give it a blurb, or at least acknowledge my work in a note, something like that. I knew he had other projects going on, and I’m not presumptuous enough to think that what I create must be made into a film. In fact, aside from Whompyjawed, I’ve always thought my books would be tough to film well. That said, once the ball got rolling on Tideland I was delighted, amazed, and a bit doubtful. Still am, actually. I’m also pleased that Jeremy Thomas is producing it, because he’s worked with many of my favorites, people like Takeshi Kitano and Nagisa Oshima.

I take it you were a Monty Python fan as a kid.

Absolutely. I first saw Python as a second or third grader in Dallas. It completely altered my reality–I’d never seen anything like it, but it also made sense to me, in a way that also made no sense whatsoever. (laughs) Does that make sense? Anyway, I think Dallas was one of the first cities in the U.S. to show it on TV, so this was probably 1977, maybe earlier. It was shown on Sunday nights, and because my mother liked it too, I was allowed to stay up past my normal bedtime to watch it. That alone guaranteed a tremendous amount of devotion from me.

Favorite Monty Python sketch?

Lord, there’s just too many. The Fish-Slapping Dance never fails to crack me up. And Terry Jones sitting naked at the organ, something about his expression and bare ass, go figure. The exploding sheep, too.

At what point did you become aware of Terry Gilliam’s films?

The first one that impacted on me was Time Bandits, and it impacted on me in a big, big way. I was living with my father by then, in Santa Fe, and I must’ve seen the film every night that it played. In fact, my dad would pick me up from school, we’d do errands and eat, and then he’d drop me at the theater. This was before we had cable TV and a VCR, of course.

Even though your work is occasionally experimental, your novels tend to be character driven and much more literary than fantasy. Why do you think a director known for his surreal, fantastic take on things picked Tideland?

Well, it just appealed to his sensibilities, or his insensibilities, I guess. Actually, Tideland does mix elements of fantasy with the real, and I guess that combination gives it a slightly more surreal edge over my other books. But if you look closely at something like Branches, it has those elements as well. When I was writing Tideland, I spent a lot of time reading about and looking at the work of Andrew Wyeth. Now I make no mention of Wyeth in the acknowledgements, and I didn’t use any of his imagery in the text. But I was trying to put the feeling his art gave me into the marrow of the book. Later, after Terry read it, he mentioned that parts of it reminded him of a Wyeth painting, and I was amazed. No one else before or since has made the connection, but he did. So apparently he was able to visualize those elements while reading it–that mixture of the natural and the surreal, the juxtaposition of images–and maybe that’s what grabbed him. I don’t know for certain though.

At what stage is the film version in?

I’m not really sure. I suspect it’s at the we-need-money-pronto-to-make-it stage, so we’ll see. It’s a long, potentially gnarly road from where it is now and the big screen, and a good number of things could just prevent it from getting made. But the script is done, and I think Tony Grisoni did a great job at compressing the book and making it film worthy. So far they’re staying pretty faithful to the novel, but I hope to god if it’s made Terry will embellish and add and turn it upside-down somehow.

Why would you want that? That’s a pretty rare thing for a writer to say.

Well, because I’m a fan of his films, and if it’s made I’d like to sit in the theater and not be too aware of the fact that it’s based on my book. For that matter, I have absolute faith in both Terry’s and Tony’s artistic leanings, much more so than my own and most others. So I want to see a Terry Gilliam movie, not a Mitch Cullin book. Really, I’m a much bigger fan of what he does than I am of what I do. In fact, it’s probably fair to say I’m not a fan of Mitch Cullin at all. I mean, Christ, I see him every day, and naked too! He can really be a moody fucker. Still, he’s mostly a nice guy, just gets on my nerves at times. But what can I do, other than die (laughs).

Is that true? You don’t really like what you do?

Oh, I do for the most part. It’s hard work, you know. It’s just not much fun, and I certainly don’t curl up with what I write, feeling all giddy and full of delight about my books. That’d be a bit masturbatory, wouldn’t it? And not in the best sense. It’s a strange road, I suppose, because I’m not sure I had much say in this writing life. It’s like I stepped into a room over fifteen years ago and shut the door–meanwhile relationships ended, new ones began, people died, my friends got married and some had children–and I end up emerging one day, staring at myself in the bathroom mirror, thinking, “Where’d my hair go?”

Going back to Tideland, have you had any input in the film?

You mean in terms of it being realized for the screen?

Yes. As well as ideas about the script, actors, things like that?

No, not really. I’d rather stay out of that one. If asked, I offer my two cents, but the truth is, that sort of stuff is a bit premature at the moment. Actually, I did read through the first draft of the script, and prior to it being written Tony asked if I had any research that might help him get going, so I sent over some articles and photographs I’d used while writing the book. Sent him some music too, if I recall. Not sure how helpful that was, though. Actually, I recently sent Terry some CDs of my pal Howe Gelb’s music, thinking there might be something there he could use for the film. Other than that, I’ve tried my best not to be a pest. There are few things more annoying than pesky writers, really.

Even more annoying than pesky journalists?

Okay, you got me there. Pesky writers are actually third, right after pesky journalists and pesky waiters.

What about pesky editors?

That’s right, I forgot. Pesky writers are fourth then, right beneath the editors.

Besides lurking regularly on the Dreams website, Tim Woo is a freelance writer living in Los Angeles. When he’s not busy as a pesky editor/contributor for LIT. (formerly The ALR Quarterly), he tends to bore crowds with poetry/performance art.