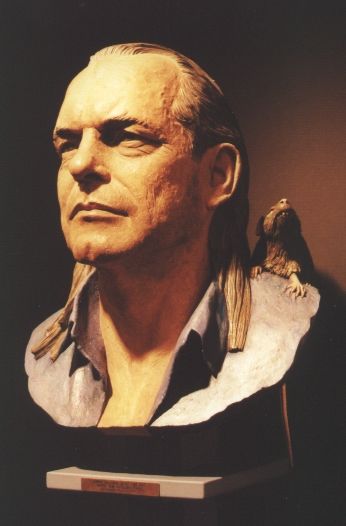

Terry Gilliam and the Rat with the Golden Tail, by Val Charlton – a bust touring with the Devious Devices exhibition

Terry Gilliam has taken a break from filming Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas to put on an exhibition of automata. He explains all to Penelope Dening of The Sunday Telegraph, in an interview published on 25 January 1998. The photographs of the automata on this page were taken by Phil Stubbs.

“The earliest cartoons my mother ever kept of mine were of Martians that looked like household appliances. Like a Hoover that I turned into an extra-terrestrial. I was just playing around. But it was clear that I was taking things that were there in front of me and inflicting on them other qualities that were never intended.”

Terry Gilliam’s face beams like a cartoon sun. His fascination with surrealism has never left him, and now he finds himself back at the cog-and-lever end of the spectrum – automata. Automata are mechanical fantasies in which common mechanisms are adapted to make incongruous machines that appear to have a life of their own.

Gilliam’s involvement came as a result of one of the coincidences that he says map his life – Ralph Steadman talked him into fronting an exhibition of contemporary automata, Devious Devices. The coincidence is that Gilliam is currently in the final stages of editing Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and Steadman’s hallucinatory illustrations were an integral part of Hunter S. Thompson’s Seventies classic.

While Steadman has joined forces with engineer Keith Newstead to produce the largest piece in the show (the Newsteadman Automaton – 3m high), Gilliam’s role has been that of seed planter. Each of the 18 automata is the maker’s response to an object chosen by Gilliam to be in some way symbolic of the 20th century.

Automata Maker: Jon Mills

Object given by Terry Gilliam: Test Tube Baby

A sculptural metal automaton on the theme of genetic engineering

“I think maybe people were expecting something much cleverer,” he says. “But I didn’t think that was part of my job. They’re the clever people. So we had a telephone, a psychiatrist’s couch, electric guitar, cine-camera, atomic bomb, V1 rocket, test-tube baby, radio, a computer, a space-ship and so on. Boring things. But I wanted to make them mundane because then they’ve got to be really inventive – taking mundane things and making them interesting. It’s back to surrealism – taking the ordinary and looking at it in different ways you wouldn’t normally look at it.”

The inclusion of a toothbrush is less obvious. It’s there, he says, to represent America’s obsession with dental hygiene. In a typically surreal aside, Midwest-born Gilliam confesses that one of the reasons he fell in love with England was because “perfect teeth didn’t exists here”.

Gilliam is wary of perfection, and it’s the flawed aspect of automata – central, he believes to their power to disturb – that continues to fascinate him. “Like puppets and masks, they’re not the thing they’re purporting to be. There’s a synaptic gap of some sort where things don’t quite touch, and in the space between those two things comes thought.

Automata Maker: Sokari Douglas Camp

Object Given by Terry Gilliam: Psychiatrist’s Couch (with a book about Freud and a postcard with a picture of Freud’s counselling couch)

The psychiatrist on a couch and a patient on a chair

“It was so basic to what are considered primitive societies. But I think they’re actually more sophisticated societies than ours. Ours is losing a strange sophistication because everything that is fed to you is literal: there’s no need for you to be engaged.

“It’s like the difference between theatre and television. Theatre is abstract. Television is not abstract at all. Our culture has somehow become something just for the elite to remind themselves of ancient ways of storytelling.”

Children, he believes, have the right idea. His own nine-year-old son, “like every other kid”, watches cartoons in preference to just about anything else. “And cartoons are abstract.”

Wallace and Gromit, he points out, is hugely influenced by the complex inventions if Heath Robinson. “He could take the most incredibly mundane household things and turn them into part of this elaborate machine that would wake you up, brush your hair and bathe you or whatever. That’s what’s so wonderful about them – the enormous effort that goes into this thing that you would normally do effortlessly. And that’s the other way of doing automata, creating incredibly complex paths to get to something incredibly simple.”

Although Gilliam fights over the Nintendo with his son (“I love flying spaceships”), he sees the opacity of computers and virtual reality as ultimately numbing to the imagination. “You can’t control things. You can’t feel part of the process.” With automata, the mechanics are the point.

“It’s almost like doing my animations on Python, which clearly weren’t perfect. It wasn’t like Disney where everything is seamless and smooth and articulated. With automata a cog turns there, a lever goes click there. Everything moves on Newtonian principles and it always feels like, well, I could maybe do something like that. You can always have the chance of being a mini-god, to create something that apparently has life.

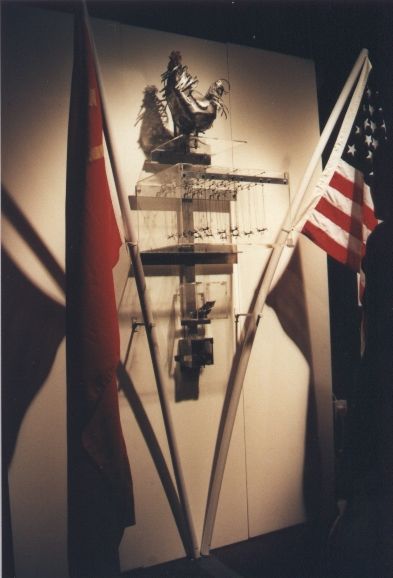

Automata Maker: Rachel Higgins

Object Given by Terry Gilliam: Stars and Stripes/Hammer and Sickle

Communism and Democracy – steel, brass, copper, perspex

Automata have been around for a long time, starting with the Egyptians who made tomb figures with limbs moved by levers, via medieval mechanical clocks with articulated figures, to 19th century parlour pieces, such as mechanical birds – reaching their populist heyday with the coin -operated arcade machines of the 1930s.

The action of a coin continues to exert its fascination today and modern automata-makers are increasingly used by museums and other penurious institutions to design witty ways of relieving visitors of cash.

Although Gilliam’s movies now use computer-generated images, the director is still happiest “just getting a piece of paper, getting a stick of wood, a bit if this, sticking them together and making them do things” at his special-effects company workshop in Covent Garden. He knows he should use the new technology more, “but I don’t get the same sensory thrill. There’s no smell, there’s no sound, there’s no texture. With computers I feel sensorially deprived.”

Irony is a central element in automata and Gilliam sees “that kind of humour” as the touchstone of a confident society. “It’s surrealism at its best. Funny and disturbing. It sparks off so many different emotions. I’ve always found the ability to laugh at the most serious things is a test of how important they are.” (Gilliam went through college on a Presbyterian church scholarship, intending to work as a missionary: “I eventually drifted away because the people in the church didn’t have a sense of humour. I said, “What kind of god are we trying to worship here who can’t take a joke?”) As a kid, he built worlds in his bedroom out of balsa wood. Now he builds worlds on film.

“That’s why I do films, in a sense. Trying to create worlds and trying to control them. It’s architecture without building regulations and fire marshals.” For Fear and Loathing, the worlds Gilliam has created are as surreal as ever. “Vegas in the Seventies didn’t exist any more. And Vegas in the Nineties didn’t really like us. So you end up creating a world.

“Again it’s not a literal world because you’ve got a couple of druggies running around. But that’s why I’m attracted to those kinds of things. You take at one moment what purports to be the real world and then you start distorting it and fiddling with it. This we’ve done for a low budget so there’s a lot less of my normal fiddling about with things. But I think it’s still pretty twisted.”

As well as being a showcase for automata-makers, Gilliam hopes the exhibition will encourage people, especially children, to think “I could do that.” To become those little gods of their own worlds.

“It’s immediately achievable and understandable. We get lost in a world now where things are too big and too vast and not specific enough. And people are kind of lost about what to do and where they fit in and how much influence they can have on things. And as things get more complex, you have to simplify. As Europe becomes a unity, regionalism becomes stronger. It’s the only way humans can function. So perhaps automata are the hope for the future.”

Devious Devices at the Croydon Clocktower, Feb 4 – June 4; then Wolverhampton and Manchester.

Dreams thanks Adrian Sturges for providing information of this event.