Terry Gilliam invited a crew to make a documentary of the making of Twelve Monkeys. This became a movie called The Hamster Factor and Other Tales of Twelve Monkeys. This page features a few Hamster links and tells the story of the docu through an exclusive Dreams interview with the directors of the documentary, Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe.

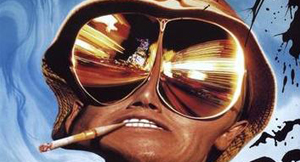

Stills from The Hamster Factor

Other Hamster Factor pages in Dreams

An article from Neon magazine about the movie (coming soon)

A press release produced by the filmmakers (coming soon)

Interview with Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe

Phil Stubbs: Who decided that The Hamster Factor should be made? How did you get involved in the project?

Keith/Louis: When Terry came to Philadelphia in November of 1994 to begin pre-production on 12 Monkeys, he wanted to find someone who would shoot a Hi-8 documentary about the production of the film. He set his assistant Lisbeth Fouse on the job of finding someone, and she contacted Sharon Pinkenson, the director of the Greater Philadelphia Film Office. Sharon gave Lisbeth contacts at all of the local film departments, one of which was Temple University, the program in which we were finishing up our master’s degrees. One of our professors, Warren Bass, called us up and said, “Would you guys be interested in being put on the list of people to be interviewed for this project?” He thought we would make a good team since we had worked together before and since we already had a Hi-8 camera. We of course said “Yes!”

When Lisbeth called us regarding an interview, she said she was really only looking for a single person to do the project. But we felt pretty certain that the project was really too big for one person alone and told her to at least consider us as a team. After setting up an appointment for an interview, we cut together a demo reel of our work, clips from short films we had done individually as well as together. It was a pretty strange mix of quirky doco excerpts from four pieces: Keith’s Ben Franklin(s): A Historical Fiction — a documentary about Philadelphia’s competing Benjamin Franklin impersonators; Keith’s John The Barber — a documentary about a philosophising neighbourhood barber; Lou’s Roadside Eulogy — a documentary about people’s emotional responses to having run over animals with their cars; and Lou’s Jean Meets The Beatles — about a woman who met the Beatles when she was a teenager in London in 1963.

During our interview with Lisbeth, we stressed how much we thought the project really needed a team of two people. Of the people interviewed, we were the only pair of filmmakers. After the interview, we gave her the demo tape and then left. Outside of the production office, we were pretty convinced that we didn’t stand a chance at getting the project — Lisbeth seemed to suggest that one person hanging around the set was going to be obtrusive enough and that the producers would probably totally veto the idea of two people. We were pretty dejected about the whole thing because in the days before the interview we had really begun to feel that the project had all the makings of a great documentary, especially if the production of 12 Monkeys went anything like what we had read about Gilliam’s troubles with Brazil and Munchausen. But on our way to our car, Keith spotted Terry through one of the windows of the production office. He was in the middle of a large meeting with the producers and crew. Lou had no idea which one he was, having only been exposed to the Python skits on the radio. So, we left feeling that no matter what, at least we had gotten to see Terry Gilliam. Little did we know!

A few days later, we got a call from Lisbeth. She said that Terry had really liked our demo tape and wanted to meet us. We assumed that this would be a second level interview and were pretty nervous about the whole thing. Lisbeth had us wait in his office for about 15 minutes until he was done with a meeting, during which time we grew even more anxious. But, when he finally showed up, he was disarmingly casual: “Hello, gents! So, what do you think about doing this documentary?”

What were your initial thoughts about making a movie about a Gilliam movie?

From a documentary standpoint, we were excited about the potential for conflict. We were very familiar with “The Battle of Brazil” and hoped to find some similar disaster/catastrophe story. As fans of Terry’s movies, we were also really excited about the chance just to watch him work. For independent filmmakers, he is quite an inspiration in the way that he works on the fringes of the Hollywood system but still retains such a strong personal vision.

What was your first impression of Terry when you met him and how did your opinion of Terry change over the course of your movie?

Our first meeting with Terry was pretty mind-blowing, not so much because it was Terry but more so because he was so unexpectedly casual and candid. And he was like this throughout the making of the documentary. Amidst all of the tension and paranoia of a Hollywood production, Terry was always very casual and open with us, which was really great for being able to keep things in perspective and not get too discouraged when things weren’t going well. His candour was also really wonderful from a documentary perspective because he didn’t guard his feelings about how the process was going: he wasn’t afraid to tell us when he had no clue what he was doing!

What rules did you have to obey?

Because we were on the set at Terry’s request, we pretty much had unlimited access. Hollywood films are very hierarchical, and we were below the production assistants — essentially below the lowest rung of the ladder! Our strategy tended to be “Stick close to Terry” because we knew that no one would bug us when we were near him.

As documentary filmmakers, you never want to be obtrusive, and we really worked hard to keep low profiles so that we could linger about unnoticed as much as possible. There were times however, when the actors wouldn’t want us around because they were trying to get into character, and we would usually try to stick around as long as possible until someone asked us to leave. We did have an agreement with Terry and Chuck Roven, the producer, that if anyone asked us to leave a particular set, we would. At first, this type of situation felt like getting kicked out (which it was), but as people became more comfortable with us being around, they would just walk over to us , tap us on the shoulder, and politely ask if we didn’t mind not filming. As it happened, that didn’t even occur very often, probably because one of the conditions of our contract was that Terry, Chuck Roven, Bruce, Brad, and Madeleine all had a right of approval over the finished documentary. So, it was always clear that everyone was protected in case we turned out to be crazed exploitative sensationalists.

What was your relationship with the three main stars?

Brad Pitt is Keith’s tenth cousin four times removed on his mother’s side. Madeleine Stowe’s father’s sister-in-law (her aunt by marriage) is Lou’s seventh cousin twice removed on his father’s side. And Bruce Willis is Keith’s eigth cousin three times removed on his father’s side AND Lou’s ninth cousin three times removed on his mother’s side. Our on-set relationships to the three main stars were similar — very very distant.

What were your thoughts about the UK?

We spent three weeks in London during the editing of 12 Monkeys and our impressions of it tend to be shaded by the fact that the editing process was such a pleasure to be around compared to the production process. During production, we always felt like we were in the way of this giant network of people trying to accomplish something, and the experience was very stressful. But when we arrived in London, we already had an established relationship with Terry, who just said, “You’re here to shoot, so roam around through all of the editing rooms freely.”

Also, with an editing staff of about a dozen people, the atmosphere was much more intimate and friendly. On the set, the Craft Services woman always passed us by when she went around with her tray of cappucinos. But in the editing room, every one stopped everything at around 3:30 and had a cup of tea and some relaxed conversation. It was so civil!

The next time we returned was in November of 1996 for our premiere at the London Film Festival. And that too was a real treat. Our reception in the UK has proven to be quite a bit more enthusiastic than in the States, probably because of the higher concentration of Gilliam fans. People in the States have responded well, but the amount of press coverage we’ve gotten in the UK – primarily due to our Associate Producer Lucy Darwin – has really made our visits to the UK a lot of fun.

How did you prioritise what was in the final cut of your movie?

Once we started editing, it became very apparent that the strongest material in the 135 hours of our footage was the stuff pertaining to the test screening and its aftermath. Accordingly, we wanted to structure the documentary so that it reached its peak at this point. Identifying that material as the strongest also helped us figure out what exactly was the strongest story in all of material. We had spent a lot of time documenting the genesis of certain sets and costumes and many other more standard “making of” aspects of the production. But for us, the most dramatically compelling material had to do with Terry, his perception of himself in relation to the Hollywood system, and his own internal creative conflict which presented itself as a bit of a “cinematic mid-life crisis.” Once we had identified this conflict as the main story we were going to pursue in the footage, a lot of the material became irrelevant.

When Terry saw the finished cut of the documentary, he seemed a bit embarrassed that it was so much about him and not more about the collaborative process. But, as we told him, his story, more so than the nuts-and-bolts of the joint effort to make the film, was what we found most interesting and compelling. There are probably many different documentaries that could have been made from 135 hours of footage. The Hamster Factor just happened to be the one that we were most interested in.

Were you rewarded well?

We consider ourselves really lucky regarding The Hamster Factor. The sale of the completed documentary to Universal not only gave us international distribution for our first feature-length film, but allowed us to cover all the costs of the film and have a small amount of money left over as a very very modest salary for two years worth of work on the project. It’s very rare for no-budget independent filmmakers to come out of a project and not be in debt. Of course, working for two years with next to no money and our credit cards charged to the max was not a pleasant experience. But luckily, it paid off in the end.

Also, at the risk of sounding corny, the opportunity to do the project was a bit of a reward in itself. Not only did we get to observe Terry at work and get a true warts-and-all look at the movie-making process, but the high profile of our subjects opened a lot of doors for us in terms of publicity. As an independent filmmaker, you tend to struggle to find an audience, screening opportunities, and press coverage. With The Hamster Factor, that sort of exposure has come a lot more easily. That’s not to say that the only merits of the documentary are in its subject matter but rather that the subject matter helped spark people’s interest in taking the time to actually watch the documentary.

What was the most important thing you learnt while making the movie?

Watching Terry go through the struggle of trying to achieve his vision and then having to question it in the face of negative test screenings was a really inspirational lesson about making movies. It’s probably best summed up by the tee-shirt that Mick Audsley, the editor of 12 Monkeys, wears in one scene of the documentary: “ART IS: Working on something ’til you like it, then leaving it that way.”

And the most amusing thing about the whole process?

One thing that really surprised us when we started watching 12 Monkeys being made was that the psychological process of making a big budget Hollywood film is very similar to what we had experienced making our small student films. The only real big difference is the amount of digits in the budget, which of course adds levels of stress exponentially. Other than that, you pretty much see the same sorts of excitement, insecurities, self-doubts, etc. It was a very equalising experience to see the camera crew watch the first roll of rushes with the same nervous excitement that we had felt (and continue to feel) with our own projects. Of course, the opposite extreme occurred when we saw how depressed everyone got after the initial test audience didn’t respond well to the film. We go through those same feelings with our own projects, however we realised that all of those budget dollars don’t protect a filmmaker from that experience but actually make it worse since there is much more at stake.

What career advice would you offer to Terry?

Work with more hamsters. Regard all documentary crews with great suspicion.

What future do you forecast for Terry within the Hollywood system?

When we last saw Terry in March, he was telling us about his attempts to get The Defective Detective underway. Strangely enough, we told him that it just didn’t seem like the right thing for him to be doing at the time. We told him he should try something like a psychedelic road movie about journalists in Las Vegas.

What other movies would you like to have gone behind the scenes at?

Fellini’s 8 1/2, Truffaut’s Day For Night — After having made a film about people making a film, it seems that the logical career move would be to make a film about people making a film about people making a film.

What are you working on now?

We are trying to develop a couple of different documentary ideas and some feature-length scripts, but nothing is really concrete yet. It is only recently that a lot of our publicity work on The Hamster Factor has slowed down and we have been able to start thinking of other projects. Whenever people ask us this question, we like to say that it is like asking a woman who has just given birth when she is planning on having her next child. That excuse is getting old though, so pretty soon we’ll have to get something solid underway. It’s still probably a bit soon for a 12 Monkeys re-make!