The director speaks with Phil Stubbs on the location of his latest picture The Man Who Killed Don Quixote

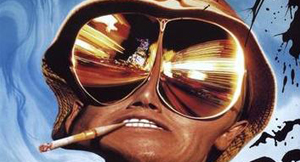

Terry Gilliam first started working on his Don Quixote project in 1989. It finally started shooting in 2000 with Johnny Depp. Yet production was halted after six days due to an injury sustained by the film’s Quixote, French actor Jean Rochefort. Gilliam never gave up on the project, and many years later he started shooting “The Man Who Killed Don Quixote” in Spain and Portugal with Adam Driver, Jonathan Pryce and Stellan Skarsgård.

I interviewed the filmmaker in Tomar, Portugal, at a beautiful convent that dates back to the 12th century. The film was scheduled to spend two weeks at the convent, mostly shooting through the night. The interview took place at around 5pm, just before the preparation for that day’s shoot was about to start. Early shooting at Tomar had been painfully slow, and the production work there was already one day behind schedule.

My plan was to spend two weeks on location: one week in Tomar and one week in Madrid. The objective was to conduct interviews with cast and crew to aid the picture’s publicity upon release. My task was cut short, however, since just before midnight on the day of this interview, I fell down some poorly-lit convent steps and broke three bones in my left foot. An ambulance trip to two local hospitals was required, and my time on location unfortunately came to an end.

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is released across UK and Ireland on 31 January with special event advance screenings on 23 January, with Terry Gilliam Q&A. To buy tickets, go to www.quixotemovie.com

Phil Stubbs: What is it about the character of Don Quixote that has caused you to be so determined to make this picture?

Terry Gilliam: I think the problem with Quixote is that once you get hooked on that character, and what he stands for, you become Quixote. You march into the madness determined to make the world the way you imagine it is. And of course it isn’t!

Can you tell me about the story of the picture and how it’s changed since the 2000 attempt?

When I was first working on the script of Quixote, immediately after I’d read the book, I realised how difficult the project would have to be. It was originally an advertising man, an advertising director who actually ends up in the 17th century. It seemed to me a modern advertising guy is a perfect example of what Quixote actually isn’t. Because advertising people sells dreams, whereas Quixote believes them – there’s a difference.

Advertising is rather a corrupt form of dreams and I thought I would take a modern character to guide the audience through the story, because the modern audience is probably not going to recognise the difference between the 17th century and the 12th century. Both funny clothes, armour, that kind of stuff. So I thought a modern character would be our guide to where we were.

I was bored with it after our first attempt , and thought there’s another, more interesting, way to do it: it was about films and filmmaking, and what films do to people, in particular those who are involved in the making of a film. And so our advertising guy has been transformed into someone who made a film 10 years before called The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. And they filmed it in a little village in Spain with local people and 10 years later he comes back to that village and thinks it’s going to be wonderful and as fabulous as when he was working there – and he finds out most of the people in the village don’t like him.

He’s destroyed many lives. In fact the character who he got to play Don Quixote, a little shoemaker has gone mad and actually thinks he is Quixote. So it all takes place in the 21st century as opposed to a time travel film.

What are the themes in the script that are important to you?

The dangers of filmmaking! It’s about betrayal. It’s about corruption, it’s about dreams and the power to transform the world… a lot of things, I’ve forgotten what they all are, and they probably won’t be in the film when I’ve finished!

How did you manage to get the green light for the production this year?

It’s been just a long battle of trying to get financing. It’s a time when we are the wrong budget, it’s about 15 million dollars – it’s the wrong number. You need to ask for 100m or 10m, and you’re more likely to get the money.

It’s been difficult patching it together. A lot of presales to various distributors, state money from Spain. And ultimately a friend of Amy, my daughter, who has put up several million to help us. It’s really been the result of somebody who had enough money they wanted to see the film get made, and were willing to gamble their own cash!

Turning to the look of the film, how has Goya’s work inspired you?

I always start with some artist, whatever film I’m doing. On this one really there’s two artists. There’s Goya, because his work is extraordinary, and it’s Spanish. And the other is Gustave Doré who illustrated Quixote in the 19th century and those images have always stuck with me.

It’s this battle between the precise image of Quixote and his world, and the dark, phantasmagorical and disturbing world of Goya. I don’t know what we’ve got in the end, but it’ll be something! But not necessarily either of them, but both are starting points for when we started working on the film.

You have incorporated more than the look from Las Fallas, the meaning as well. Can you talk about the inspiration from Las Fallas?

Many years ago I went to Valencia. They have a fiesta called Las Fallas. Basically all the town, and all the little communities in the town raise money in the year, and they build these amazing tableaux. They are satirical, political, religious, and incredible. They are made from papier-mâché, they’re huge figures. The biggest one is probably about 30 meters tall. And they’re very elaborate and they stand for a week throughout the town and then on the last night they’re all burnt.

So there’s this idea of sacrifice – of people working hard spending money and building these incredibly beautiful complex creations… and then burning them.

So Santa Cathartica came out of that, and the difference with ours is… because the original Madonna has a torso, but the Madonna’s skirt is a wooden construction that people bring flowers to, and then slowly build a skirt out of flowers on this big conical skirt.

And our big conical skirt is slightly different because rather than beautiful flowers, we’re hanging all the things that people don’t want anymore: the bad things, the broken things, the corrupted things – whether it’s a children’s toy or an old chair or a television set. They are basically sacrificing their consumer goods on Santa Cathartica.

Santa Cathartica at Tomar

I understand you’ve used Uccello’s work within one of the rooms.

Yes. There’s one room that we decided to establish the sense of a hunt, a battle. So there may be other themes going on in this – they may not be physical, they may be mental. Benjamín Fernandez the designer, picked out some lovely Uccello. I started with some Belgian and French tapestries to start the process: the killing of unicorns, a mythical image. He translated that into Uccello which has been recreated by our friend Daniele Auber who has worked on many of my films since Brothers Grimm.

We’ve got banners around Cathartica, and in the castle that is the finale of the film. All of the fabric artwork was created by Eduardo Hidalgo, who has been dressing the sets and his team. They are their own invention and they are amazing. They are not the kind of thing I would have ever designed, I’m not capable of it, but they are amazing.

Can you tell me about what Adam Driver has brought to his role?

Adam Driver is just an extraordinary actor. I’d only seen him in a couple of films, and in one of them he was wearing a mask – Star Wars, so I didn’t get much to see of him. He was suggested, and we had a meeting. It was one of those totally immediate, instinctive reactions. There were various people who had tried to play the part over the years, in the various iterations, but here was a guy who didn’t look like all the people I’d seen. His unique look to him, the unique quality about him, and I just thought: this is the guy.

And I still haven’t seen any of his really good films, I’ve made a point of it. I like the idea of just reacting to a person, and what they’re like in the flesh, and thinking those are the qualities this character needs. I was right – let’s put it that way – he is fantastic.

Adam Driver and Jonathan Pryce

Jonathan, you’ve worked with him before – what has he brought to his character?

Jonathan has been waiting to play this part for about 15 years, ever since our first collapse. He was never right, I felt. He was too young, and then he was too busy and finally he was free, he wasn’t travelling the world playing a Shakespearean character, and he hit 70 years of age. Perfect…and on he came. I keep thinking that every Shakespearean character he’s played in this Quixote, from King Lear to Hamlet to Shylock… they’re all in there. The great thing with Jonathan, he is a great comedian, he’s incredibly funny. I’ve never seen him have so much fun on a set, that’s all I can say – he’s loving it.

Stellan – could you tell me about working with him?

Stellan Skarsgård is another actor I’ve always wanted to work with. In every film he’s in, he just stands out as being real. I never feel there’s any fakery with him, he’s just stunning whatever the character is. We met a few years ago at some awards ceremony briefly for about two seconds. In the flesh, he’s even better, so I asked him to play the Boss, who is a kind of a father figure to Adam’s character, and is betrayed by Adam in various ways. I thought he’d be great, and he is. He’s just a joy to work with because there is no actorish-ness about him, there’s just truth and to see him transform himself from himself to the character in the blink of an eye is extraordinary. The entire crew responded to the first scene he’s in. He steps out of a car and that’s all it took. The Boss was there, and he was terrifying.

And Olga…

Olga Kurylenko plays the Boss’s wife, who seems to have a little fling with our hero. She is a blonde unlike her normal dark look. She’s always been beautiful but I’d never seen her be as funny as she is. Last night we were doing a night shoot and she had me in hysterics. She’s just brilliant beyond anything I’ve seen of her, and for people to see in her as effectively a dumb blonde, it’s something they’ve never seen before.

And Joana Ribeiro?

Joana is playing the romantic lead. Joana is a young Portuguese actress who I was just introduced to in Portugal. She had done television work, so is not tremendously experienced, but it was one of these instinctive moments for me and I’m really pleased because she’s got the fire, I wanted somebody with Latin blood in them. She’s got these extraordinary eyes, that burn in to you. She has had in many ways the toughest time because she’s up against these very experienced actors, and she’s got to hold her won. She’s doing it and I think she’s going to be a fantastic star one day – if not in our film then the next one.

Can you tell me about the costumes in the party scenes here at Tomar, the story behind those?

Well we have this big party in the castle, which is in effect Quixote’s dream come true. It’s Renaissance/Medieval, it doesn’t matter – somewhere in that period that we wanted to play with. It’s about Quixote arriving and being at this party and it’s everything he’s ever dreamed of. We had to make beautiful costumes, and Lena Mossum, I don’t know how she’s done it. We’ve got a small budget for what we have produced. It’s quite beautiful and we didn’t have to be accurate. We had to be beautiful and flamboyant, so I gave her a lot of freedom to play.

How pleased are you with Quixote’s nose?

This was the most important thing of this film, to get a good nose on Jonathan. Because Jonathan’s nose is a lovely little nose, but it’s not the hawk beak that Quixote must have. The prow of a boat plying its way through the seas of disaster. We got one, a very good one.

How was shooting on day one?

It was terrifying starting shooting this film – finally, after, well it originally started in 1989, that’s a long time ago. To be thinking, dreaming it, writing and rewriting it, it was a horrible feeling because all you can do is fail. You can never achieve the amount of stuff that’s in my head, that I want on film. We started it and somehow we’re getting there. What’s interesting about a film, at a certain point it starts making itself, so it’s not actually the film I set out to make. This is a slightly different film. It’s doing its own work, I’m just holding on for dear life.

Was there a point where the pain of the past, where were you able to box it away?

I’ve never quite put it away. I remember Mike Nichols said this years ago when I asked him about directing films and he said: every day is a disappointment, it’s never quite as good as you’d imagined it. But it’s good enough hopefully, and you reach a point – it may just be tiredness or just an acceptance of reality – this is what it is. It’s making itself and if it doesn’t work, it’s the film’s fault, not mine!

What has been the happiest moment?

I don’t know if there are any happy memories when you make a film. The happy moment is when you finish it and it works out. Everything up to then – it’s just a struggle to maintain sufficient optimism to think you’ve actually achieved it. And controlling the pessimism which is far more powerful than the optimism!

The Three Giants