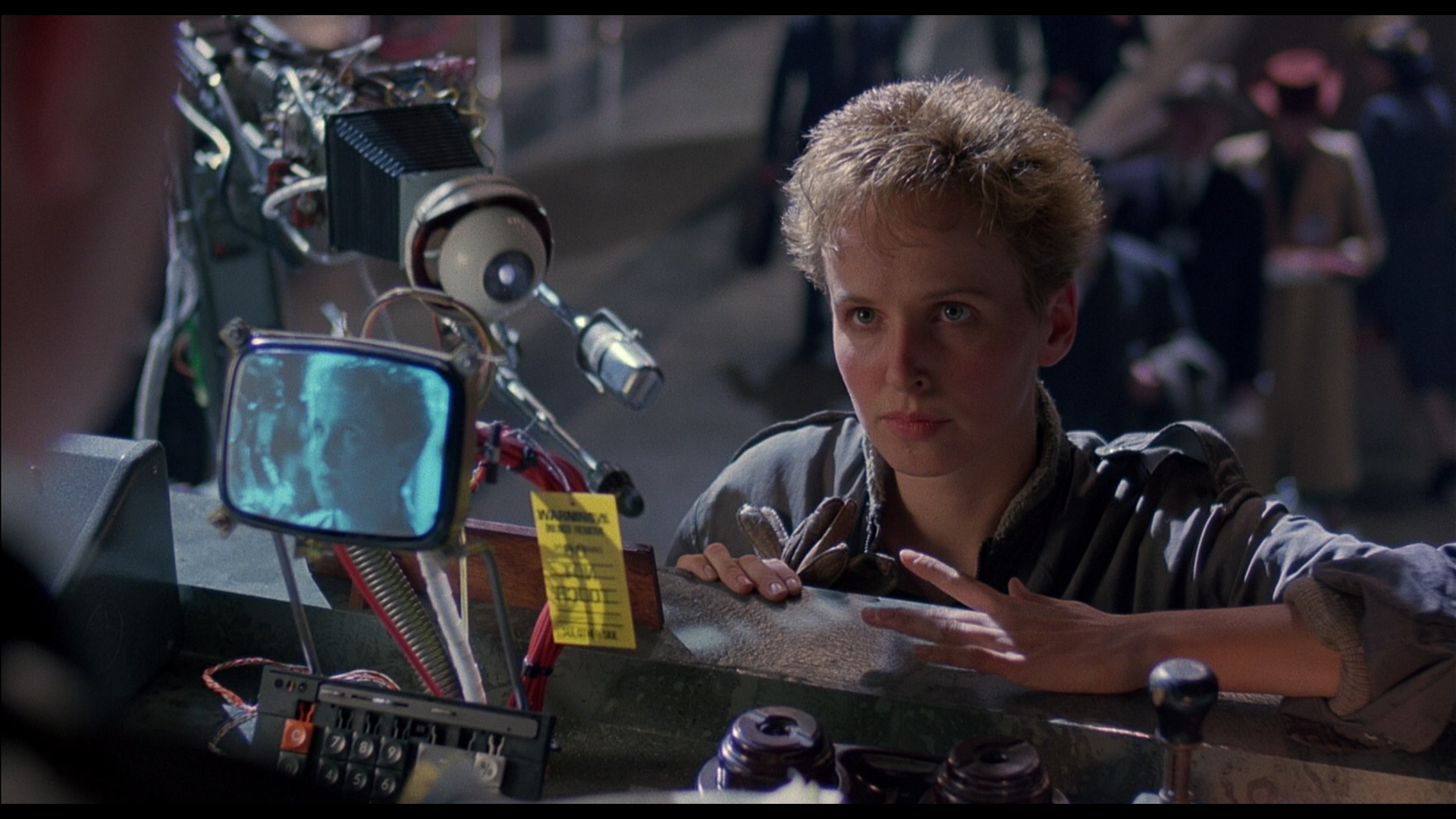

Having always been ‘the other Python’ – the Flying Circus’ unseen American animator Terry Gilliam has recently come to the fore as a film director. His new film, Brazil, is a spectacular and only partly comedic vision of the future.

Interview by Paul Mathur, for Blitz magazine, March 1985

Photograph by Mark Collicott

“HI, I’M ME, who are you?”

The ‘Me’ is a bluff 45 year-old American with five o’clock shadow and a fairly disgusting jumper. He is also a film director responsible for, amongst other things, part of an occasionally anarchic comedy movement, a film about pirates and parents, and, most recently, a film which Steven Spielberg described as his innermost nightmare. The man is Terry Gilliam and the new film, a natural progression from Python, Time Bandits et al, is called Brazil.

In a Covent Garden cutting room Gilliam is putting the finishing touches to quite the most frightening movie you will see this year and desperately praying that I don’t ask him why the film is called Brazil. Fortunately I’ve no intentions of doing so. The film, evoking the same city as 1984 but scuttling down a far more interesting subway, is far too smart to slip into such easy analysis. The suggestions as to ‘why Brazil?’ are there for all to see, but, for now, are best left unarticulated. Instead Terry and I sit and bandy a mixture of common sense and snappy mistruths.

When were you first inspired to make Brazil?

“It must have been around the time that I was doing Jabberwocky. I was in Port Talbot looking for locations and went to this beach which was absolutely black because it was where all the coal was brought in on a conveyor belt. The sun was going down and I thought of this image of someone on the beach watching the sun go down and listening on a little portable radio to all these lush, romantic latin songs. That’s where it all began and I’d written scripts of it before even Time Bandits, but no one was interested. After Bandits came out there seemed to be a lot of interest in me, so I thought, ‘What the hell, now’s the time to unleash this film that no one wanted to know about’. Tom Stoppard came in to do some restructuring and then Charles McKeown and here it is now!”

How different is the finished article from the original conception?

“In spirit it’s exactly how I envisaged it. The central theme is still the dreamer working in a reprehensible system who becomes victimised by the machine he’s a cog in. It’s almost like a continuation of Time Bandits in a way the kid hasn’t quite grown up but the world has become a dangerous place. It was nice to stop having to be funny all the time and, instead of being nice and sweet, just go for the jugular!”

There’s certainly a lot less straightforward ‘This Is Funny’ material than in your and Python’s previous work. I mean, Michael Palin as a torturer?

“I loved the idea of him doing that. It’s like Palin is the nicest person in the world, and yet here he’s totally playing against himself. Peter Vaughan as well. He’s usually pretty obviously horrible but we’ve got him, superficially at least, as a gent. I think that has far more impact, it’s the charming people who are ultimately most evil. The film does start funny and with a lot of laughs but by the end it’s not just a comedy. Usually we can hide ourselves behind comedy but I thought it was time to expose oneself a little bit more and do things I feel a bit more strongly about. It is a funny film and I’d hate it any other way, but it’s also rather a disturbing one”.

To what extent were you goading people on, daring them to laugh?

“Oh there was that! The idea of it being both the spoonful of sugar to help the medicine go down and also the way to catch people in mid- laugh. I wasn’t sure when I was making it what level to take, but in the end I think it does work. The fact that you’re laughing through it makes it all the more disturbing that this horrific thing can be just a big joke.”

There is an obvious delight, dear readers, in discussing a film you know nothing about, but it’s probably not a great deal of use to you so here’s a few pointers:

It’s a tale of confusion and bureaucratic destruction.

It’s meant to be set in Christmas 1984 but could be Easter 1933.

People die in it.

People fall in love in it.

It’s bound to be compared with 1984.

It’ll scare the pants off you and give you an irrational fear of local government.

Is that any better? Such coyness is not wilful elitism but rather a recognition that over- elaboration will spoil things. A little taste and a lot of clues is enough.

Is it a depressing film?

“I really don’t think so. It started off from the premise of taking things to their logical conclusion, so there’s obviously quite a lot of sad conclusions. What makes it ultimately hopeful though is the human characters themselves. One of them who ends up as a blob after plastic surgery is ALWAYS OPTIMISTIC and I think that’s important. She’s the one character in the film whose lesson above all others I would like to heed!”

Can comedy still function within a framework of taking things to conclusions? Perhaps that’s all comedy in fact is?

“We did want to do a film to see how much we could get away with. We’d done it before it was a major motivation in Python but we’d never really played with the edges of comedy and tragedy rubbed together. It was very exciting.”

All the characters are taken to the edge. Take the part played by Robert De Niro for example. He sweeps out towards self parody and for much of the film is just A Robert De Niro Figure and yet by the end he becomes an incredibly poignant hero. Did such nobility surprise you?

“In a way, yes. He is literally destroyed by paperwork, the thing he hates most, and as he goes down he does become a tragic hero. The image of someone consumed by paper was there right from the start but I don’t think the role (Harry Tuttle, Renegade Heating Engineer) was so important.

“By the time of the film though, it had got a lot clearer. Tuttle becomes the tragic hero and dies in order to maintain the film’s central figure (Sam Lowry, dreamer and bewildered cog, played by Jonathan Pryce) and his process of growing up. In order for Lowry to grow up he has to divest himself of everything, including his heroes.

Gilliam is someone who knows De Niro as ‘Bobby’, something that to Nerophiles like me begs intimate questioning and a hunt for gossip.

What level of commitment did he have to his part? How did he apply himself?

“Well Bobby’s a perfectionist and even though it’s a very small part in terms of time he had to get everything right. He had a whole mock-up of the set built and learned exactly how to use all his heating repair tools! I told him that he should use his tools like a surgeon would his, and next thing I knew he’d got in touch with a surgeon friend and was going down to a hospital in New York to see operations being performed!”

It seems very odd for him to be in the film at all.

“Well I really liked the idea of having an incredibly famous person in the film but concealing him all the way through. He’s in a balaclava most of the time and then when you finally do see him he’s only there for a split second and he’s gone. One person who saw it in Paris without credits or anything didn’t even realise De Niro was in it!

“That sort of a role really appealed to Bobby though. He’s never played a bit part before and he didn’t want this one to be like one of Frank Sinatra’s walk-ons, where everyone gasps and says, ‘It’s him!!”

Considering the atmosphere of the film, with its retro-future tag, it’s bound to be put alongside 1984. Does that upset you?

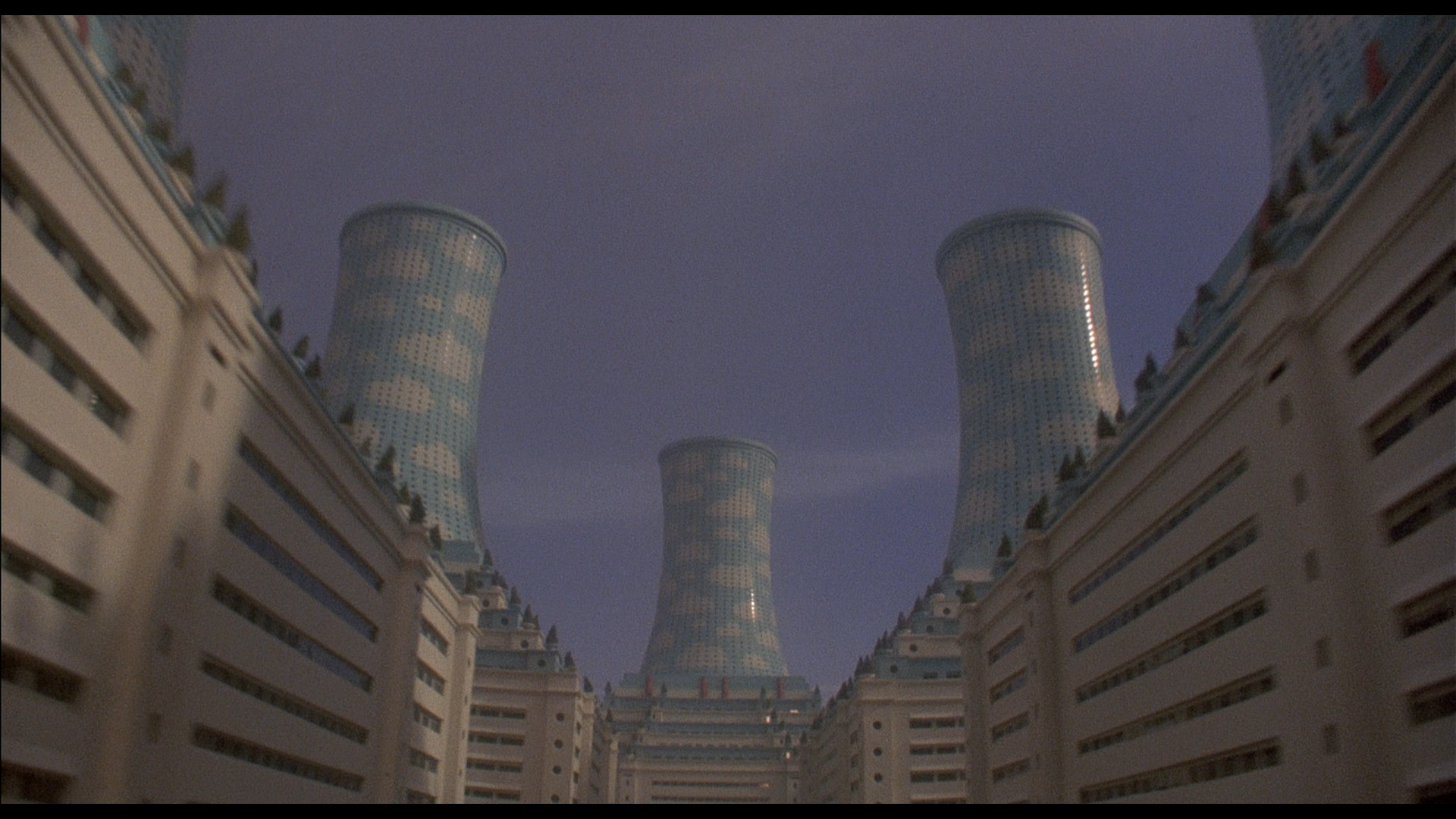

“Well, for a start we began the film before them but it was weird that we both went for the same mood. I wanted the time of the setting to be unspecific, anywhere in the twentieth century. It draws on a lot of things and mixes a lot of technologies and attitudes. There’s much of the spirit of the science magazines of the forties, all promising a great future. You know, all that ‘Learn Electricity And Make Millions’ stuff. The ideas, though, are taken further so that they don’t work out right for the people trying to use them. I used to be able to shut interviewers up in their tracks by describing it as a ‘post-Orwellian view of a pre- Orwellian world.’”

I plough on. There’s an awesome sense of human responsibility at the heart of it all.

“Well, that’s what I think separates it from 1984. I’ve seen both and I find one of them lacking in humanity. But I’m not telling you which.”

Go on.

“I just don’t BELIEVE 1984. Nothing is there, you can’t get food and yet there’s these huge video screens on the walls. What I was trying to do was play around with elements and ideas that we can already understand and relate to. It’s more effective because it’s closer to us and yet we still can’t get it to work for us.”

It is at times overpoweringly dark, hence the regular fantasy scenes. How has this been met in a business concerned with entertainment?

“Well it certainly seems to affect people whether they like it or not! Claustrophobia seems to be the dominant emotion. One guy said he couldn’t sleep for days; he was this middle-aged lawyer with his life all neatly sorted out and my film was the last thing he wanted to have to cope with. I thought, ‘Jeez, he’s paid his money to see it, the least he should expect is a thrill or two!’”

Do you feel an empathy with the Steven Spielbergs and Joe Dantes of this world?

“I enjoy that catharsis of adventure but I don’t like the transience of what they do, they’re just like fairground rides. It’s been that sort of young audience, though, that has been able to cope best with my films. When we were doing Time Bandits the executives were complaining to me about the way that the parents get killed in the end. Then a seven year- old came out of the screening and said that was the bit he liked best. It’s everyone’s fantasy to dispose of their parents! Likewise in Brazil it’s been the younger audience that has been able to handle best the fact that there isn’t a traditional happy ending. The American bosses want it clear cut and simple but the kids expect a little more. Film makers patronise children far too much. One kid wrote to me and said it was the first film he’d seen that he could have passionate discussions with his date about; he’s getting laid because of me!

“I like playing with what is acceptable and enjoyable, putting ordinary things in and making them special. There’s a burning body in Brazil and it seems shocking, whereas it’s commonplace in lots of films. A valley is a valley is a valley but when you see one in Brazil after two hours of walls and darkness, you think, ‘My God, a valley!!’”

Has a similar approach of seeing what you could change around always run through your work?

“Well with Python there was a novelty that came through our constantly aspiring to mediocrity but never being able to afford it! In Holy Grail for example we would have liked horses but we were too poor so we used people with coconuts and it turned out much better!”

Is there a future for Python?

“Not as much more than a drinking club. At the moment we’re all concerned with different things, like I don’t want to be an animator anymore. The only thing we have in common is our desire to take something other than the easy route.”

What plans have you for yourself?

“I’d like to do something less intense if I’m actually capable of doing so, which at the moment I’m beginning to doubt! Perhaps a remake of the Baron Münchausen story. He was a braggart adventurer who told incredibly tall stories and swore they were fact. There’s a lot of potential for something light and frothy, although I’ll probably be able to bring my death obsession into it.”

Why are you staying in Britain when you’re obviously in demand?

“Basically because of my fear and loathing of America, particularly Hollywood. Obviously it would be quite exciting to play the exec over there, all that macho bloodlust is rather thrilling. In the end, though, there’s no purpose, all the time spent on mind games could be better utilised getting the job done. Also I have a perverse fascination with Britain. I find it hard to imagine a nation more intent on self-destruction!”

The tape clicks and all good things come to an end. I urge a last quote on the nature of his craft.

“Most of the time when I’m making films I’ve no idea what I’m doing!”