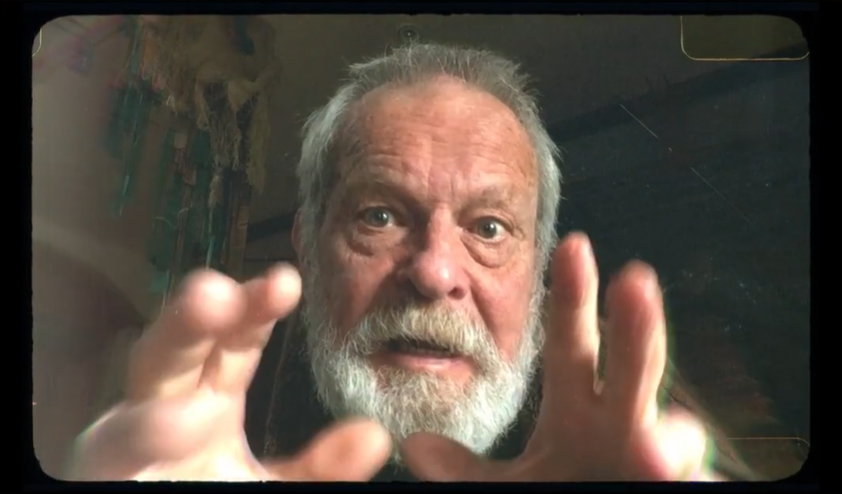

Here is a transcript of the press conference held recently to launch Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in the UK.

Ben Evans was there, and asked a couple of the questions. He made a transcript of the press conference, and sent it to Dreams.

Q: What was it about Fear and Loathing that made you want to do it?

TG: The chance to do something so disgusting, so awful that it was guaranteed to make sure no-one goes to the cinema.

Q: Did you actually like the book?

TG: The book is extraordinary. When it arrived, we seemed to be on the same wavelength, in the sense of frustration, madness and disappointment in America at that time. His generation really did believe we could change it all. Silly us. By the 70s, it was all broken and that book is a reaction to that. The quote from Dr Johnson in the front of the book is what the book is about.

The thing that amazes me most about that book is that Ralph Steadmans drawings are so much a part of the whole, yet Ralph wasn’t there. He was just some Welsh git in England.

Q: Hang on.

TG: It wasn’t the “Welsh” that was important there. It was “git”. It was just Ralph. He had nothing to do with that world and yet he captured it somehow. He showed a similar kind of anger, frustration.

Q: Do you feel there’s any duality between the end of the 60s and the end of the 90s?

TG: There’s a connection, that’s why I did make it, to throw it out there, as a part of the world we live in. As an artifact. A reminder of the times. The problem now is that people strike me as very frightened, very timid. They don’t want argument – they want consensus.

It’s hard. I felt that kids needed something to remind them that you could actually go beserk. You could feel so strongly and behave badly, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Unpleasant for the person sitting next to you perhaps, but it’s a way of dealing with things. Rather than taking Prozac and taking the edges off experiences, the tops and bottoms.

Prozac’s like a Big Mac. You’re getting something which is taking the extremes away, but is nice and safe in the middle. A Big Mac is not excellent. It’s shit, but it’s a safe way of living. I just felt things were getting more and more constricted.

A lot of kids have energy and nowhere to go with it. Pent-up energy and nothing to do but take E and dance all night long and then collapse.

But that’s not the same thing that was going on at the end of the 60s. We were luckier. It was easier and clearer – the way to fix things that were wrong seemed clearer.

I love the wave speech in the middle of the film. When I was doing the research for it and getting into the documentary footage, I realised I’d forgotten the impact of thousands of people on the streets, doing things and we don’t see images like that any more. That was the way it was.

The 60s and 70s have been so pooh-poohed of late. “Bunch of flower-power druggies.” That was not what was going on and I felt we needed to right the balance somewhat.

I’m not sure we give people a picture of what they should be doing with their energy but there is now one more choice available.

Q: Is it a pro or anti-drug film?

TG: What do you think? It was very funny in the States, for making a “pro-drug” film. I don’t think it’s pro-drug at all. What it is doing is being honest. Showing the good and bad sides. The whole film has ended up being a strange kind of drug trip. The opening with the speed and “BOOM!!”, the stuff kicks in. It’s great and it’s fun and there’s all this stuff going on and then it starts to get really ugly and starts shifting on you. You’re in that hotel room and you feel like you’re never going to get out of that dark place.

Then you escape and you’re out in the desert. We’re drawn back to Vegas and it gets even weirder second time around. You see all these things and you decide. That’s my whole attitude to the thing. I think those drugs are a bit more interesting than Prozac.

Q: You said “Imagination is the thing that allows us to control the world around us.” In Fear and Loathing, it seems the hallucinations are in control.

TG: It’s an extension of the same thing. It’s about inventing realities. Imagination is one way to do that, but you still have to watch out for a number 14 bus. No matter how imaginative that world is, along comes the bus and runs you over. Drugs, especially in the 60s, were used as ways of adventuring, of heading out, experiencing new things and looking at the world differently.

The truth of the matter is, I haven’t taken any of those drugs. My drug intake is: coke twice, hash and pot a few times, and amyl nitrate once. That’s it. I can do all that stuff without drugs, which has always intriuged me. I thought that when people were taking acid and peyote they were suddenly seeing the world in this extraordinary way. I was hoping that they would learn to do that without having to rely on the chemicals. I’ve been lucky because I saved all my money.

The we talk about drugs now is crazy. The drug I like most is strong Italian coffee. That’s an incredibly powerful drug. When coffee was introduced to this country, coffee houses were like the hash houses of Amsterdam – they were drug dens. People knew how dangerous coffee was back then. It’s a dangerous drug, folks.

Drugs alter things. They alter you, in different ways. You have to decide what you want to do and how much you want to be altered. How much of it’s useful, how much of it’s negative. That’s the choice. The difference is that some drugs are legal and some are illegal and it tends to be bureaucrats who make those choices. Some drugs support Swiss multinationals and some support Colombian peasants. You Decide. You can make the choice.

In a sense, the film does that at the end. The last speech is about that – the part about acidheads thinking you can buy peace and understanding for $3 a hit. Well, you can’t. You have to work at it. We live in an age where we buy everything. You shouldn’t always buy. Sometimes you have to experience.

The speech is about individual responsibility. Nobody is minding the light at the end of the tunnel. Just you and me. There is a point to this film. By going through all these extreme experiences, the character hopefully comes out a wiser person, but it’s still all about him choosing what he wants to do.

Q: You have said that you’d like the world to take a more grown-up view of drugs. Is Fear and Loathing going to help?

TG: (laughs). I don’t know. But, just as we don’t talk about the censorship of the marketplace, we don’t seem to talk about all the legal drugs. They’re accepted and that’s OK. I think that’s a nonsense.

Q: The music is very influential on the atmosphere. Why no “Sympathy for the Devil”, which is a recurring theme in the novel?

TG: We couldn’t afford it. It cost $600,000. And, to be honest, we tried to make it work at the begining – because you’re right, it opens the book, and it’s a theme. But it didn’t have the energy we need at the start of the film. We put it on, and the driver was like “Cool”, instead of being the Bat Out of Hell. So it just didn’t work, and that’s why we put Jumpin’ Jack Flash at the end – just for all those people who were waiting for the Stones somewhere.

Q: You said that “we live under economic censorship – that you can’t make a film unless people are going to watch it.”

TG: I was at a film festival in the Czech Republic a year ago, when I said that. I was just talking to the kids and everybody there who were making films under the Communists, with heavy censorship, but it tended to be about petty things. You got around the censorship by being oblique and clever.

I’d always complained about that but in many ways, it was maybe less bad than the censorship of the marketplace. If it doesn’t make billions of dollars it doesn’t get made. Because films cost money to make and because the people making the decisions are only interested in money – they’ve no cultural remit or interest in anything other than making as much money as they can. This limits the kind of films that get made.

In many ways I’d almost prefer the Communist censorship – you can get around it by being clever. This way, you can’t be clever or talk about interesting things because you have to make money. But nobody ever calls the marketplace a for of censorship.

Q: Have you got around that now? After 12 Monkeys you could surely make any film you wanted to because that was so sucessful.

TG: No, I can’t – because I can’t make the one film I really want to, because it costs X amount of money.

Q: What is it?

TG: I can’t talk about it or else it won’t get made. It’s one of the reasons I did Fear and Loathing, because it collapsed at the last minute.

Q: How did the direction of the film change with the influence of Messrs Depp and Thompson? Everyone says Depp’s a method actor, but if he really did all those drugs, he’d be dead.

TG: What he’s got up his nose is lactose. Powdered milk. I kept saying that by the end of the film, he’d be capable of breast-feeding the entire crew. Johnny isn’t a method actor – he’s a thorough actors and immerses himself totally, but most method actors carry it with them. We say “Cut” and they’re still in character, and that’s not Johnny. It’s like working with an English actor, we’re talking about football and “Action” and he’s into character, then “Cut” and we’re back to telling jokes again. Benicio’s more of the method actor in that sense. He wouldn’t break character and would stay in it, living it day and night.

Working on the set, because we had limited time and money, we just had to work fast and people had to be on their toes, and you can’t do that smashed out of your brains.

Q: Would you say your films were optimistic or pessimistic?

TG: I would say they were all optimistic, even Brazil. I set out to make Brazil and I said “Can you make a film with a happy ending where the man goes insane?”. The fact that he could stay alive and well in his imagination seems to me more optimistic than not, but not by much.

It’s like “Is Fear and Loathing a pro or anti-drug film?” I don’t want things to be black and white, which is what I think most films tend to do – give simple answers. I would rather raise questions. Each one of you decide what you make of it.

The difference between 2001 and Close Encounters has always amazed me. At the end of 2001, there’s a strange room he’s in. You end up almost with a question at the end and you can’t explain it all. It leaves you with lots of unanswered things trailing around in your head.

Close Encounters, Spielberg comes out with these little people in latex suits. That’s dumb. That gives you an answer. I’d rather do films which leave questions unanswered, so you can talk about it. I suppose I’m trying to encourage discussion.

Q: You constantly cross the line between insanity and sanity and blur the distinction. What’s the fascination?

TG: I don’t know the answer. I’m just using these films to find my own way in the dark. Again, encouraging people to look at the world around them in different ways sometimes. No more than that. One of my most pleasurable moments was watching Fisher King in NY, with an audience of New Yorkers. They came out of the cinema and looked at the city in a completely new way.

That’s fantastic. People saying “I never saw that or thought of that before.” That’s what I thought (if I can use that awful three-letter word) “Art” is all about – encouraging you to look at it in a different way. In Brazil, people didn’t seem to notice all the ducts around them before. Take the ceiling away and what’s behind it, folks?

We live in a time when we are constantly barraged by What The World Is; politicians, everyone telling us that This Is The World, and it’s like this, and defined in that way. There is all this stuff that doesn’t get talked about, and it’s usually the madmen, the Holy Fools, the drug addicts who get out there and find out what’s on the edge.

I could be making films which give you nice simple answers but it doesn’t interest me, because everybody else is doing that. That part of the road is well-covered. I’m looking at what’s happening out here on the verge and I don’t know what’s out there. I don’t understand surrealism except that it sets up juxtapositions – your brain firing to try and make sense of this thing.

Q: Do you think Hollywood has got too middle-of-the-road?

TG: Of course. They’re looking for Lowest Common Denominator – the biggest audience. That’s what they’re after. You find individual film-makers within that who get away with more , but that’s what you’re fighting against. Hollywood’s a factory. They produce things in large numbers for large numbers of people. They’re not offering choice. They’re offering more of the same and it’s pushing out the other views of the world, and I hate that.

American films are 85% of the market. That’s very bad. You want local culture to be alive. Local stories, local ideas, local perceptions of the world, and all of that is just being pushed out.

Q: Have you ever seen a film that you particularly wish you’d made?

TG: The last one was Unforgiven – Clint Eastwoods film. I came out of that cinema going “Fuck. If I could make that film, I’d die happy”. A lot of people don’t understand why I felt that, but I did. A great, great piece of film-making.

Q: You said Hollywood is ignoring things that are important. Is there anything at the moment that you’d like to make a film about?

TG: I would never do it that directly. Things are always worrying me, bugging me, obsessing me, but you’d never see them done directly.

Q: So, you might do them subtly?

TG: I don’t know if I could do anything subtly. It’s the one thing they never accuse me of. Surprisingly enough, one of the audiences the film has worked really well with are 14-15 year old kids. I thought this would be a college-age film but young kids are saying things like “Best Film I’ve ever seen” – a real overstatement, but it means something. People are putting it down – saying it’s just because it’s drugs and wild living. But the kid said: “No, it’s not that. It’s because it’s honest.”

Q: Does it bother you that they won’t be able to see it here?

TG: They’ll see it. Don’t worry. Any smart 14-15 year old will see it. They weren’t allowed to see it in the States either – it’s an R. It’s interesting, though – the word “honest” – because I think the biggest thing we’re living in now is an age where hypocrisy rules. There’s such bullshit out there. Less so here, but it’s catching up with America. I used to think the UK was 10 years behind the US, but now it’s maybe 5. The UK seems too intent on catching up with America.

Q: Clive Barker said that there were 2 kinds of fantasies – one where our mundane reality is invaded by something else and it causes small, localised changes – and there are the fairytales, where you have multiple colliding realities all at once. Is your work a fairytale?

TG: If I’ve only got two choices, I’ll go with the fairytale. Kids have always liked my stuff. Adults want everything explained to them, kids are much more open – the world hasn’t closed in on them yet. The doors haven’t shut yet on all these possible worlds that are out there. The adults get frightened if it isn’t clear.

If you’re going to choose a fairytale – The Emperor’s New Clothes is my favourite because only the kid can see that the emperor is really naked, the only one who’s innocent enough to say the truth. Everybody else is lying to themselves to cover up the fact that he surely can’t be naked.