Click here for Production Story, Chapter Four

ANIMAL MAGIC

Responsible for the horses and donkeys on set were Richard Cruz and his son. The Cruzes had six weeks to prepare the horses and make them accustomed to a film set environment. Gilliam was thrilled by the horses. “They’re fantastic! Ricardo senior and Ricardo junior are brilliant.”

Working with horses scared Gilliam not only because of their unpredictability, but also due to the need to protect Jonathan Pryce. The actor, in his late sixties during the shoot, says, “I hadn’t ridden a horse for at least ten years, and I told Terry I didn’t think I could do very much riding, especially that which is demanded of Quixote.” Gilliam recalls, “We were all being very careful because Jonathan was very worried. In fact, we were all worried, because we had to keep him injury-free for the whole shoot.

“In Oreja, on the day Quixote was to charge the windmill, we shot it with Jonathan’s stunt double, but turning past the camera, I could see he was a stunt double. I said, ‘Jonathan, do you think you could just ride a little bit, through the turn?’ We’d reached the end of the day and Jonathan said, ‘All right, I’ll give it a go. Just that bit?’ So, we started him down the hill. Jonathan goes full gallop, charging up the hill, with lance in hand, took the corner brilliantly, lowered the lance, shouted and headed towards the windmill. The whole crew stood up and applauded. Jonathan knows how to do this kind of stuff; he’s a theatre actor. He waited until the last moment and just blew everybody away.” Pryce confesses, “It’s always a good move to tell a director you can’t really do very much. Then he’s pleasantly surprised and grateful when you actually do it. He did curse me for showing off!”

POSTPRODUCTION

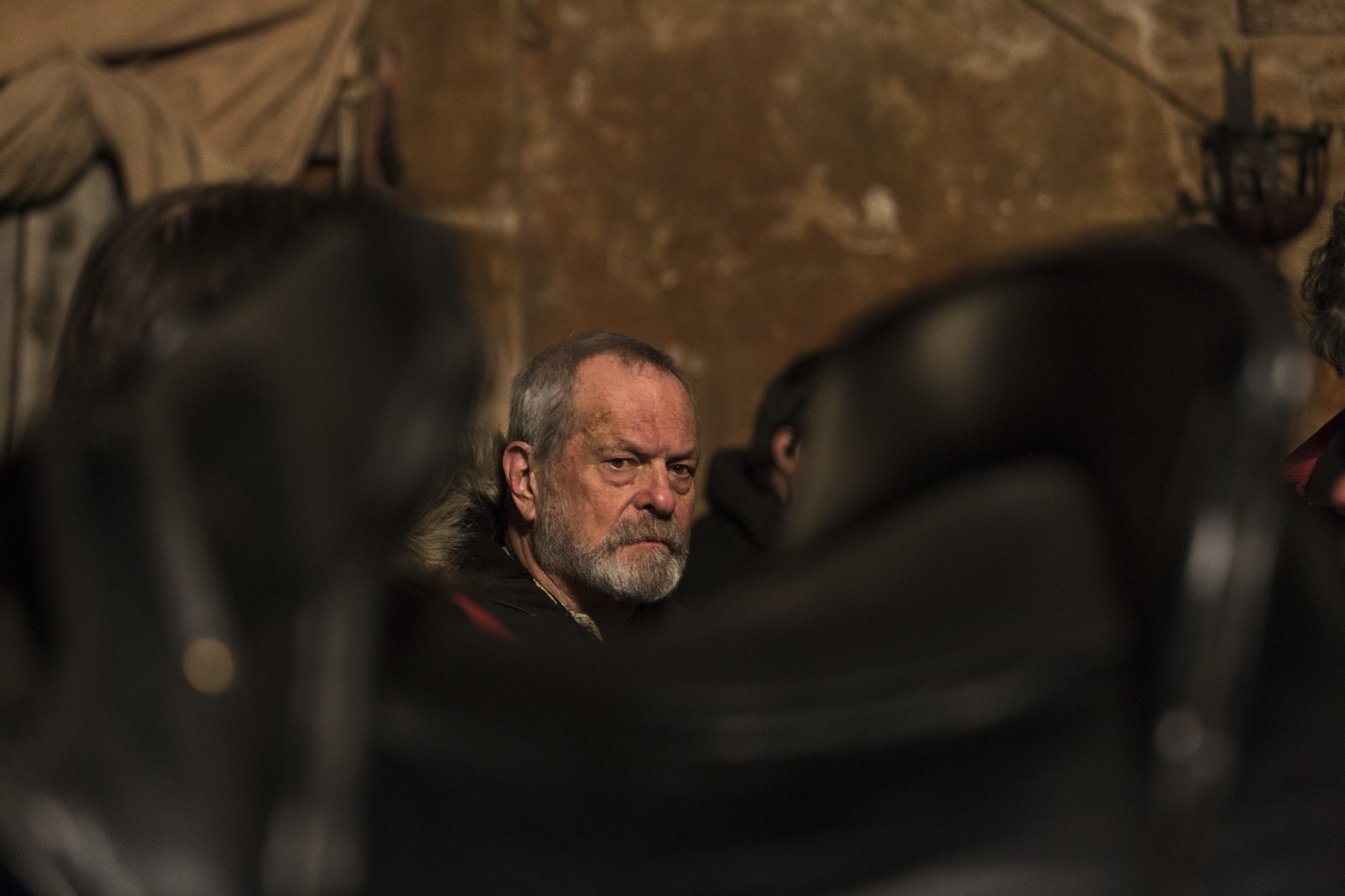

During the shoot, experienced Madrid-based editor Teresa Font took the daily footage and prepared an assembly cut. Font recalls, “I was given so much good material, and my first reaction was to ask myself: how could a foreign director be so faithful to the spirit of the novel?” One key responsibility was to provide quick feedback to Terry Gilliam on how the shots worked together. This was not an easy task since, according to Font, “I had to work hard going through all the material because there are so many things going on at the same time!” Font found the project a very rewarding experience, with plenty of praise for the actors, particularly the two leads.

Responsibility for editing the film then passed to Lesley Walker, who had worked with Gilliam before on several pictures, and who had been due to edit The Man Who Killed Don Quixote back in 2000. Walker recalls, “At the beginning of 2017, Terry phoned me up and asked me if I would like to edit it. Without question, I said yes!” The assembly edit was used as a basis by Walker to create the first cut, which was three hours long. Says Walker, “The first cut was far too long. I think of it as a doughnut really – it had a very soft centre. So, we had to get rid of an hour, speed it up and take lines out that are not necessary. And I had been very languid with some of the countryside in the first cut, so I knew I could speed that up.”

MUSIC

Early in 2017, composer Roque Baños received a call from the Quixote team while he was in Los Angeles. Baños recalls, “The first thing Terry said was that he wanted to experiment! Terry knew that the music had to have a Spanish flavour, and he also knew that he didn’t only want orchestral music. He wanted to experiment with ethnic instruments that would have existed on Spanish soil. We had a great experience using an oud – an old guitar – and also a flute that was made from the horn of a bull, which sounded like a recorder. And we had all different kinds of percussion.”

It was clear to Gilliam and Baños that the score should be a representation of Quixote’s feelings and delusions. The composer says, “Quixote really believes that he’s a hero, and that he’s been chosen to do good. So, when we see him, we have to feel what he feels. Every word that comes from his mouth, even if doesn’t make sense, has to be truthful. We have to feel it that way; we have to feel he’s right.” The hardest scene to get right was when the party guests watch Quixote on the wooden horse. Says Baños, “I sampled whispers from the crowd, mixed with a choir. It’s a weird sound that creates a confusing atmosphere. We had to mix the sample with horns, with orchestra, choir and percussion. Having to make everything fit with what is on the screen was really complicated.

“For me, the best part of all this was meeting with Terry and sharing my creativity with his. Every day we had such a great time inventing, imagining, and mixing things together. He’s really enthusiastic, and I felt that way too.”

Gilliam feels lucky to have been able to collaborate with Baños. The director says, “Roque’s great strength is that he writes really beautiful romantic music. It’s never sentimental; it’s never cheap – it’s just beautiful. He’s just got a huge heart, and he’s very smart. He’s brilliant.”

IN THE CAN

Terry Gilliam reflects on the final picture, “There’s much to enjoy. Jonathan has made it very funny. He squeezes out laughs on lines, and he ad-libbed a lot. Then Adam started ad-libbing and their combination is really good. It’s very funny, but I wouldn’t say it’s a comedy, because, more than anything, it’s a romantic film. The adventures are good, we keep it lively, and there’s laughs all the way through it.”

Gilliam is also satisfied that he has been able to encompass many personal themes and autobiographical elements. Don Quixote is a character who battles for the power of imagination against the forces of reason – a theme that has appeared in much of the director’s work. Says Gilliam, “It is about dreams and the power to transform the world.”

In sharp contrast to Quixote is the pernicious corruption in modern life, especially within business and the world of advertising. Gilliam says, “An advertising guy is a perfect example of what Quixote is not. Advertising people sell dreams, whereas Quixote believes them – that’s the difference.”

A further sub-theme that Gilliam was keen to incorporate was religion. The director explains, “Quixote talks about how wonderful Islamic Spain was in the 15th and 16th centuries. When the Moors controlled Spain, they built so much – including the Alhambra. It was the most open-minded place: Moors, Jews, and Christians were there, and everybody was working side by side. Then Ferdinand and Isabella came in, they brought in the Spanish Inquisition and the fun was over.”

The beauty of Spain and its landscapes feature in this film, but also the country’s character was an inspiration: the pride, the passion and the honour. Co-writer Tony Grisoni adds, “Spain, specifically Spanish Carnival, feels a natural place for Terry to tell his story. I cannot think of any of Terry’s films that does not ultimately spiral into a dance of chaos. The juxtaposition of beauty and ugliness, horror beside comedy, are key elements of the carnival, and as we all know: no blood – no carnival.”

The finished film also includes reflections by Gilliam on his own experiences as a filmmaker, regarding what responsibility a director actually bears. He says, “The fact that Toby does feel responsible for the results of his student film is interesting, because at least there is some decency inside a man who has become hollowed out with success. This is the autobiographical part of the film. As we filmmakers come into a community, we take it over, we excite people, we lead them down the garden path of their dreams, and then we leave. We never look back.”

Yet Grisoni suggests that Toby’s guilt may be misplaced. The writer says, “I’m not sure he is justified in feeling the guilt he does feel. I don’t think he’s thinking straight about it. Making a movie shakes up people’s lives but can also enrich lives. I’ve had many experiences of lasting friendships and connections to communities resulting from filmmaking. Maybe the source of Toby’s guilt is his self-centredness, and the fact that he sold out and failed to live up to his promise. I really like his gradual taking on the responsibility of serving Quixote. It’s about Toby giving himself up to a crazy idea, something that is bigger and more extraordinary than the world he touches and sees. He’s saying that there’s a huge world out there that’s nothing to do with me, and I’ll be in second place to that world. In a way, it’s a return to those earlier halcyon days of promise.”

“When we saw the completed film, sitting in that dark room watching Don Quixote ride on the screen for the first time after 25 years of confinement in another dimension, it was really emotional,” says Mariela Besuievsky.

Amy Gilliam is thrilled that the project has finally come to fruition and is delighted by the finished film. She says, “The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is true to Terry’s vision. It contains all the passion that Terry has had for both Quixote and Spain. It wholly justifies all the false starts and the years of hard work that we have suffered to bring this project to a conclusion. This movie is full of magic and love, and I’m so happy that it will be out there for everyone to discover.”

Click here for more features on The Man Who Killed Don Quixote